Towards the end of 2022, an article titled ‘A Theological Reckoning with Bad Trips’ appeared several times in my LinkedIn feed. In it, Rachel Petersen, a student at Harvard Divinity School, attempts to make sense of her starkly contrasting experiences on psilocybin. Petersen, who received psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy as part of a clinical trial investigating its use for major depressive disorder, recounts how her initial experience was “the most religious of my life…welcoming me into my rightful place in the order of things”. Just a week later, however, and under seemingly identical conditions, she had an “indelibly harrowing” trip that left her deeply shaken, anxious, and struggling to sleep.

While Petersen considers various perspectives in an attempt to reconcile these experiences, what she does not consider, is a perspective informed by depth psychology – one that examines the impact of taking a psychedelic substance on the relationship between the conscious and unconscious mind (1). From a depth psychology perspective, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy can be thought of as a process through which consciousness is expanded, allowing, at least temporarily, access to realms of experience that have been repressed and subsequently held in the unconscious. Stanislav Grof, a prominent psychedelic researcher and theorist, first outlined this process in the 1980s when he described psychedelics as “non-specific amplifiers” of consciousness:

“In one of my early books I suggested that the potential significance of LSD and other psychedelics for psychiatry and psychology was comparable to the value the microscope has for biology or the telescope has for astronomy. My later experience with psychedelics only confirmed this initial impression. These substances function as non-specific amplifiers that increase the cathexis (energetic charge) associated with the deep unconscious contents of the psyche and make them available for conscious processing.” (Foreword to the MAPS edition of LSD: My Problem Child, October 2005, by Dr. Albert Hofmann)

Psychosynthesis, a depth psychology, provides a model and framework through which the non-specific amplification of consciousness described by Grof, and its effects, can be considered in more detail (2).

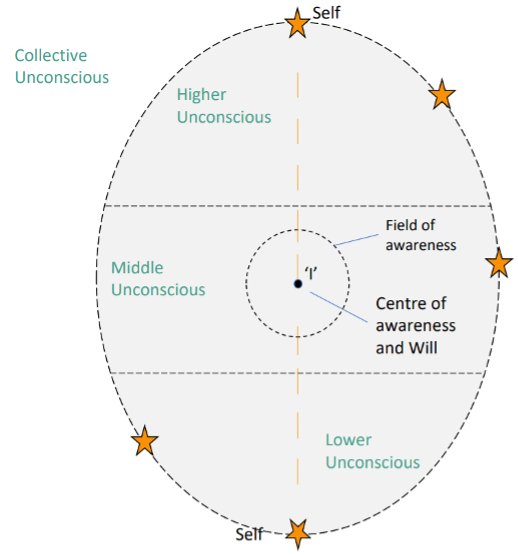

Psychosynthesis map of the psyche

From a psychosynthesis perspective, the amplification of consciousness catalysed by a psychedelic substance such as psilocybin, can be thought of as temporarily expanding the area of the ‘middle unconscious’, allowing the ‘field of awareness’ access to repressed material in both the ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ unconscious (3). In psychosynthesis theory, an expansion of the middle unconscious is understood to lead to an increase in “experiential range” and is considered a long-term goal of psychosynthesis psychotherapy (4). Firman and Gila, describing this process, say:

“…the spectrum of reality that we potentially may be aware of and respond to – expands to include more of the heights and depths of human existence”. (Firman and Gila, 1997, p. 33)

In depth psychotherapy this is a slow, painstaking process in which the therapeutic relationship is a vehicle for gradually bringing unconscious material into ego awareness. Although psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy certainly allows this to happen quickly, and in my experience, to a degree that is not easily reached otherwise, it may be that there are advantages to a more titrated approach that are precluded when using psychedelics, such as more enduring access to the newly expanded experiential range.

What is important to understand here, however, is that from Grof’s perspective, psychedelics expand consciousness in a non-specific way. They do not preference one type of experience over another but rather increase the overall energetic charge within the unconscious. This means that experiences that were previously held out of awareness in the lower unconscious are just as likely to be accessed and brought into awareness under the influence of a psychedelic as experiences held in the higher unconscious.

Firman and Gila go a step further than Grof and suggest that there is a balancing function that takes place in the psyche, where an activation of either the lower or higher areas of the unconscious leads to a corresponding activation of the ‘opposing’ area (5) – this is one potential explanation for Rachel Petersen’s experiences under the influence of psilocybin: an initial activation of higher unconscious material which then led to an activation of material in the lower unconscious. Regardless of sequencing, this process of increasing experiential range leads to an increased ability to experience all the highs and the lows of human existence: experiences of joy, grief, awe, terror, ecstasy, etc., are all made more possible. This then can be seen to result in a “life enlarged” as described by Petersen, a life consisting of more “onramps to darkness” – as well as, I would add, more onramps to light.

From this perspective, the fundamental mechanism in psychedelic therapy is understood to be the same, irrespective of the content uncovered – a ‘bad trip’ is no different from a transcendent or mystical one, other than the way in which the patient perceives it; it is all the result of a non-specific amplification of material previously held out of awareness by defense mechanisms. Or, to put it differently, repressed experiences that are judged as ‘good’ or ego-syntonic by the patient are just as likely to be unearthed as those judged as ‘bad’ or ego-dystonic.

Undertaking a therapy that amplifies consciousness and bypasses defense mechanisms in this way certainly risks overwhelm by unconscious material and related difficulties (6). Defense mechanisms are adaptive and there for good reasons, albeit often outdated ones. As Massimo Rosselli, a psychosynthesis trainer who studied with the founder of psychosynthesis Roberto Assagioli, once told me: “We must kiss the defenses – because they kept us safe.” How to work respectfully with a patient’s defense mechanisms in a context where they are temporarily rendered inert by an increase in energetic charge is a worthwhile consideration for anyone doing therapeutic work with psychedelics.

How can the risk of being completely overwhelmed by unconscious material be mitigated in psychedelic therapy? Whilst careful screening for known risk factors as well as paying scrupulous attention to ‘set and setting’ is critical, these measures cannot eliminate this risk. The personal unconscious is dynamic and by its very nature presents an unknown element of ‘set’ that cannot be controlled for in the same way as drug dosage or room temperature. In addition, practicing more organic methods of expanding consciousness and experiential range will also reduce the risk of overwhelm e.g., breathwork, meditation, guided imagery, dream analysis, etc. These activities are not of themselves entirely risk-free, however. This is not new advice – every trainer or mentor I have come across in the psychedelic therapy space has made these recommendations. Preparation of this sort is not always easily accessed however as it takes time, knowledge, and resources. Ongoing therapy in a well-held container, as I argued in my MA thesis, may also serve as a risk reduction factor in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, through the patient’s internalisation of the therapeutic relationship and the ongoing containment that this can provide, even in the absence of the therapist.

Research is increasingly showing that a disruption of a patient’s psychological status quo through a well-supported psychedelic-assisted therapy process can lead to improved mental health, better functioning, and therapeutic growth. I have been privileged in my work to witness lives improved in this way, transformed even. Nevertheless, it can also lead to severe and, at times, enduring suffering of the sort described by Rachel Petersen. Perhaps by reframing psychological wellness along the lines of psychosynthesis theory, as a “life enlarged” rather than one devoid of any suffering, a more nuanced conversation about what constitutes a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ trip can take place.

Notes

(1) Depth psychology is increasingly out of vogue in modern-day psychedelic science – despite the field being established by depth psychologists (e.g Grof, Richards, Fadiman, etc.) The current wave of psychedelic researchers prefer therapeutic frameworks based on ‘evidence-based’ therapies, particularly third-wave cognitive therapies such as ACT (see for example: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.873279/full).

(2) Assagioli didn’t reference psychedelics in his work, though psychosynthesis is referenced by others, such as Grof, as being one of the most useful frameworks for understanding the transpersonal processes involved in psychedelic therapy. See e.g., Grof, 1985 pg. 140.

(3) In the psychosynthesis model repressed unconscious material includes transpersonal or mystical experience (higher unconscious) as well as trauma, repressed memories, and ‘shadow’ material (lower unconscious).

(4) In psychosynthesis theory this is achieved through relational work within a therapeutic container and the use of psychosynthesis techniques e.g., subpersonality work (more commonly known as ‘parts’ work), guided imagery, development of the Will, dis-identification exercises, etc.

(5) See Firman and Gila’s discussion of ‘induction’, 2002 pg. 180. I am grateful to Sonal Kadchha for bringing this to my attention.

(6) In some cases, these risks are judged to be warranted – psychedelic therapies are being investigated in the main for illnesses in which existing treatments are largely ineffective and morbidity rates are high e.g., PTSD, Major Depressive Disorder Anorexia, etc.

References

Grof, S. (1985). Beyond the Brain: Birth, Death, and Transcendence in Psychotherapy. State University of New York Press.

Firman, J, and Gila, A. (1997) The primal wound: a transpersonal view of trauma, addiction, and growth. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Firman, J., & Gila, A. (2002). Psychosynthesis: A Psychology of Spirit. State University of New York Press.

Professional registrations

Contact

+44 (0)7466 393567

mail@tomshuttetherapy.co.uk